Abstract

Background

Wide variations exist in price and quality for health-care services, but the link between price and quality remains uncertain.

Objective

This paper used claims data from a large commercially insured population to assess the association between both procedure- and provider-level prices and complication rates for three common outpatient surgical services.

Design

This is a retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The study used medical claims data from commercial health plans between 2009 and 2013 for three outpatient surgical services—joint arthroscopy, cataract surgery, and colonoscopy.

Main Measures

For each procedure, price was assessed as the sum of patient, employer, and insurer spending. Complications were identified using existing algorithms specific to each service. Multivariate regressions were used to risk-adjust prices and complication rates. Provider-level price and complication rates were compared by calculating standardized differences that compared provider risk-adjusted price and complication rates with other providers within the same geographic market. The association between provider-level risk-adjusted price and complication rates was estimated using a linear regression.

Key Results

Across the three services, there was an inverse association between both procedure- and provider-level prices and complication rates. For joint arthroscopy, cataract surgery, and colonoscopy, a one standard deviation increase in procedure-level price was associated with 1.06 (95% CI 1.05–1.08), 1.14 (95% CI 1.11–1.16), and 1.07 (95% CI 1.06–1.07) odds increases in the rate of procedural complications, respectively. A one standard deviation increase in risk-adjusted provider price was associated with 0.09 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.11), 0.02 (95% CI 0.003 to 0.05), and 0.32 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.34) standard deviation increases in the rate of provider risk-adjusted complication rates, respectively.

Limitations

Results may be due to unobserved factors. Only three surgical services were examined, and the results may not generalize to other services and procedures. Quality measurements did not include patient satisfaction or experience measures.

Conclusions

For three common outpatient surgical services, procedure- and provider-level prices are associated with modest increased rates of complication rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The US health-care system exhibits substantial variation in prices,1,2,–3 spending,4 utilization,5,6 and outcomes.7,8,–9 The link between variations in price and quality remains uncertain10 but is especially important when trying to improve the efficiency of the health-care system for the commercially insured population. If higher prices are associated with improved outcomes, then policy makers, insurers, and employers must trade off the costs and benefits of high-priced providers. Paying higher prices may be worthwhile if they are associated with meaningfully improved quality or outcomes. However, if there is no association between prices and quality, or an inverse association, then efforts to shift patients to low-priced providers can both reduce spending and improve the quality of care.

At the same time, while several studies document extensive variations in the quality of care for health-care services, many of these studies focus on inpatient services.7,8,–9 As a result, they do not assess variation in clinical outcomes for many commonly received services. As surgical services are increasingly performed in outpatient settings, understanding the factors that influence the quality of outpatient surgical services has become more important.11

This study examines this question using nationwide data from the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) and focuses on three common outpatient surgical services—joint arthroscopy, cataract surgery, and colonoscopy. These services were chosen due to their frequency and the presence of existing algorithms to identify complication rates. The HCCI data includes transaction-level prices, which has been a barrier to previous studies of the relationship between prices and quality. Quality was assessed using the frequency of complications associated with each surgical procedure. For each service, the association between price and complication rates was estimated at both the procedure and provider levels.

While previous studies have examined the relationship between physician price and quality outcomes,12 to our knowledge, this is the first study to compare transaction-level prices and quality for common outpatient surgical services.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by the Bing Center for Health Economics, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, and the National Cancer Institute (R21CA219229-01). The funders had no role in the design, conduct, and reporting of this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the RAND Corporation and the University of California, Berkeley.

METHODS

Medical Claims Data

To measure price and quality for outpatient surgical services, this study used 2009–2013 claims data from the HCCI. HCCI, along with the companies providing data to it—Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare—collects medical and pharmaceutical claims data for approximately 50 million commercially insured individuals. The HCCI data includes observations from every state and each US metropolitan region.

The study sample was restricted to patients aged 18–64 who were enrolled in the same insurance plan for the entire year. For each patient, health-care utilization (the annual number of inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, emergency department visits, physician office visits, and prescription drug fills) was also measured. To further control for patient risk characteristics, the Charlson Comorbidity Index and indicators for each of the 17 chronic conditions underlying the Charlson risk score were also identified for each patient and year.13 Each procedure was linked to a specific provider using that provider’s National Provider Identifier (NPI).

Identification of Surgical Procedures

From the HCCI database, all claims for three surgical services performed in outpatient settings and related complications to these services were identified according to Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) and International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) codes. In the HCCI data, these three surgical procedures accounted for 2.5% of total medical spending, 21.7% of spending on outpatient surgical services, and 11.8% of the volume of outpatient surgical services. Cataract replacement surgeries were identified by CPT codes 66982, 66983, and 66984. Colonoscopies were identified using CPT codes 44388–44394 and 45378–45385 and ICD-9 codes 45.22, 45.23, 45.25, 45.41, and 45.42. Joint arthroscopy surgeries were identified by CPT codes 29830–29838 (elbow arthroscopy), 29862 (hip arthroscopy), 29870–29887 (knee arthroscopy), 29805–29826 (shoulder arthroscopy), and 29846 (wrist arthroscopy).

Identification of Procedure Price

Procedure prices were identified by each procedure’s bundled allowed amount for both facility and professional fees. This amount represents the negotiated price between the provider and the insurer and captures actual payments by the patient, employer, and insurer. It does not represent the “billed charge” amount, which is often not representative of the actual transacted price but has previously often been used to study provider prices.

Identification of Procedural Complications

For each procedure, complications related to that procedure were also identified and were linked to the index surgical procedure but were required to be separate in time from the primary cataract surgery. Complications related to joint arthroscopy were analyzed at both the 30- and 90-day periods following the index arthroscopy procedure.14 Complications for cataract surgery were identified by secondary surgeries as surrogate markers performed within 90 days of the primary cataract surgery.15 Colonoscopy complications were measured at 30 days and were classified as any procedural complication for one of three categories: cardiovascular, serious gastrointestinal, or other gastrointestinal complications.16 A list of the CPT and ICD-9 codes used to identify each complication is included in Online Appendix Table 1.

Additional Control Variables

From the HCCI data, provider volume for each procedure was calculated and used to control for volume-outcome relationships.17,18 To control for market-level characteristics, additional county-level data from the Area Health Resources File (number of physicians and nurses per capita, share of physicians that are specialists vs. primary care providers, median household income, share of households below poverty line, mean rent, percent of individuals with a college degree, median rent, and share of population enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid), the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey (hospital market concentration), the InterStudy survey of insurers (insurer market concentration), and the SK&A survey of physician practices (physician market concentration) were included. A full list of these additional control variables is included in Online Appendix Table 1.

Statistical Methods

Multivariate regressions were used to measure the risk-adjusted association between procedure price and the probability of procedural complications. To estimate risks of procedural complications, a logistic regression with a dichotomous outcome variable indicating if the procedure was linked to a procedural complication was estimated. To address skewness, prices in the logistic regression were standardized to the mean service-level price in each geographic market. Alternative models estimated prices in $1000 units (Online Appendix Table 3). Separate multivariable regressions were also used to risk-adjust procedure prices. To risk-adjust prices, a generalized linear model with a log link and gamma distribution was used to measure the predictors of each procedure’s price.19,20

Each regression controlled for patient characteristics and demographics, including patient age, gender, industry and insurance plan type, and medical utilization (number of inpatient, outpatient, office-based, and emergency department visits and number of prescription drug fills). Charlson scores and fixed effects for chronic conditions further controlled for patient risk characteristics. Fixed effects for year and month, CPT codes, and the 306 hospital referral regions in the USA (HRR)21 were used to control for temporal time differences (e.g., inflation), specific procedure differences, and time-invariant market-level characteristics. The abovementioned controls for provider volume, provider supply, demographics, and market power were also included. All regressions were estimated using heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors.

Construction of Provider Risk-Adjusted Price and Complication Rates

Each provider’s risk-adjusted price and complication rates were calculated using two steps and separately for each of the three services. First, the patient-level risk-adjusted price and complication rates were calculated by computing the fitted values from the respective multivariate regressions. The price of each procedure was omitted from the logistic regression used to risk-adjust complication rates. Second, each provider’s risk-adjusted price and complication rate were estimated by calculating the mean patient-level risk-adjusted price and complication rate from all patients treated by each provider with at least 50 observations.

Next, the correlation between risk-adjusted provider prices and complication rates was measured. For each procedure, standardized risk-adjusted price and quality scores that show the standard deviation difference between each provider compared to the rest of the providers in each HRR were calculated for each provider with at least 50 patient observations. The standardized scores, often referred to as z-statistics, were computed by dividing the difference between the provider’s mean value of each outcome measure (e.g., risk-adjusted price and complication rate) and the mean risk-adjusted price and complication rate for all providers in the HRR by the respective standard deviations from each HRR.22 To assess the association between risk-adjusted provider price and complication rates, the correlation between these two measures was calculated using a linear regression. Observations were weighted by provider volume.

RESULTS

Patient-Level Results

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics for the population included in this study. A total of 784,033 joint arthroscopy, 292,054 cataract surgery, and 2,968,421 colonoscopy procedures were included in this analysis. The mean unadjusted procedural complication rates were 3.22% for joint arthroscopy, 3.04% for cataract surgery, and 3.03% for colonoscopy. The mean unadjusted price for each procedure was $5484, $2063, and $1372, respectively. Patients who received these services were more likely to be above age 45. Arthroscopy patients were more likely to be female, while cataract surgery and colonoscopy patients were more likely to be male. For all three procedures, the mean patient had a Charlson comorbidity score of less than 1.

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariate logistic regressions that estimate the association between procedure-level price and the probability of receiving a complication. Column 1 presents results for joint arthroscopy, column 2 presents results for cataract surgery, and column 3 presents results for colonoscopy. For joint arthroscopy, a one standard deviation increase in price is associated with a 1.06 standard deviation increase in the odds of receiving a complication (95% CI 1.05 to 1.08). For cataract surgery and colonoscopy, the odds ratios are 1.14 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.16) and 1.07 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.07), respectively.

The adjusted percentages, also presented in Table 2, show the association between price and the probability of procedural complications, measured in percentage point terms. For joint arthroscopy, a one standard deviation increase in price is associated with a 0.17 percentage point increase in the probability of procedural complications. Based on the mean joint arthroscopy complication rate of 3.2%, the percentage point increase translates into a 5.4% increase in the rate of procedural complications. For cataract surgery and colonoscopy, the adjusted percentage point increases are 0.36 and 0.19 percentage points, respectively, which translate into 11.8 and 5.6% increases, respectively.

Online Appendix Table 4 presents results from a sensitivity test that estimate the same regression model, but includes only year and CPT code fixed effects. These results are similar to the results presented in Table 2, which include controls for patient and market characteristics. Any unobserved patient characteristics are likely correlated with the observed characteristics included as controls. Thus, the similarity between the results with and without controls suggests that unobserved confounders may have little influence on the results in Table 2.

Online Appendix Table 5 presents the results of the GLM regression used to risk-adjust prices. Time trends, younger patient age, hospital market concentration, and the share of the population enrolled in Medicaid were associated with higher procedure prices. Similarly, Online Appendix Table 6 presents the results of the logistic regression used to risk-adjust complication rates. The strongest predictors of procedural complications include increased age, a previous chronic condition diagnosis (coronary heart failure, COPD, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis), and health-care utilization (number of outpatient, office-based, and emergency department visits).

Provider-Level Results

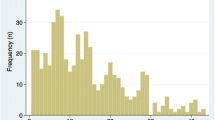

A total of 2761 arthroscopy providers had at least 50 patient observations and were included in the provider-level analysis. For cataract surgery and colonoscopy, a total of 1269 and 5545 providers met the patient volume inclusion criteria, respectively. Figure 1 shows the distribution of risk-adjusted provider prices for each of the three services. For arthroscopy, risk-adjusted provider prices range from $2706 to $11,963. The 75th percentile price, $6269, was 41.0% larger than the 25th percentile price, $4447. Risk-adjusted cataract surgery prices range from $1121 to $4027, with a 38.0% difference between the 25th and 75th price percentiles ($1664 and $2296). Risk-adjusted colonoscopy prices range from $674 to $3335, with a 40.7% difference between the 25th and 75th price percentiles ($1088 and $1531). Online Appendix Figure 1 presents the distribution of unadjusted provider prices.

Figure 2 plots the distribution of provider risk-adjusted complication rates, which are based on the predicted values of the regression results from Table 2. For arthroscopy, provider risk-adjusted complication rates range from 0.79 to 19.77%. The 75th percentile of provider risk-adjusted complication rates, 3.52%, is 32.4% larger than the 25th percentile, 2.66%. For cataract surgery, provider risk-adjusted complication rates range from 0.43 to 12.41%. The 75th percentile, 3.47%, is 45.0% larger than the 25th percentile, 2.39%. For colonoscopy, risk-adjusted complication rates range from 0.81 to 33.79%, with a 70.9% range between the 75th and 25th percentiles (4.01 and 2.35%). Online Appendix Figure 2 presents the distribution of unadjusted provider prices.

To assess the relationship between provider-level risk-adjusted prices and complication rates, Figure 3 plots the relationship between each provider’s standardized risk-adjusted price complication rate scores. Across all three services, the increasing relationship between the two measures indicates a positive association between provider prices and complication rates. In each figure, the slope of the line indicates the standard deviation association in the rate of complications for a one standard deviation increase in the provider’s price. For joint arthroscopy (panel a), a one standard deviation increase in provider-level price is associated with a 0.09 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.11) standard deviation increase in the rate of procedural complications. Both the provider price and risk-adjusted complication measures are relative to each specific geographic market, which is defined using HRRs. As shown in panels b and c, a one standard deviation increase in provider-level prices is associated with a 0.02 (95% CI 0.003 to 0.05) and 0.32 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.34) standard deviation increase in the provider-level complication rate for cataract surgery and colonoscopy, respectively. These differences persist even after adjusting for the relevant patient characteristics that impact both prices and the rate of procedural complications. Online Appendix Figure 3 presents results that are not weighted by provider volume, Online Appendix Figure 4 presents results that do not adjust for patient and market characteristics, and Online Appendix Figure 5 only risks-adjusts provider complication rates and uses unadjusted provider prices. These results are similar to the results in Figure 3.

Association between provider price and procedural complication rates for outpatient surgery. a Joint arthroscopy. b Cataract surgery. c Colonoscopy. These figures plot the association between risk-adjusted provider prices and complication rates for joint arthroscopy (a), cataract surgery (b), and colonoscopy (c). Each provider’s price and complication rate is measured in standard deviation differences relative to the other providers in each hospital referral region (HRR).

CONCLUSION

While many studies have documented substantial variations in health-care spending,4 prices1,2,–3, and quality outcomes,7,8,–9 few studies have focused on the association between price and quality.10 This study examines the association between variations in prices and rates of procedural complication rates for three common outpatient surgical services—joint arthroscopy, cataract surgery, and colonoscopy.

For all three services, this study documents widespread variation in both prices and rates of risk-adjusted procedural complications. Moreover, for all three services, this study finds a modest but positive association between prices and complication rates. The results of this study imply that a one standard deviation increase in provider-level prices is associated with a 0.02 to 0.32 increase in the rate of procedural complications. The association is strongest for colonoscopy services.

This study is not without limitations. For one, this study only used data from three commercial insurers. While these three insurers comprise the three of the five largest insurers in the country, the HCCI data does not include other populations. Similar analyses should be conducted using data from other commercial insurers, as well as the Medicare and Medicaid populations. This study is also limited to three outpatient surgical services. Future studies should examine this relationship for other services and patient populations. Second, while the multivariate regressions used in this study control for differences in patient and market characteristics, there is the possibility that unobserved differences, such as unobserved health status, may cause both higher prices and increased risk of complications. Similarly, this study uses a limited set of patient characteristics to control for potential confounders. This study does not attempt to estimate if this association is causal, and if so, the direction of this causality. Instead, these results should be interpreted as association-level results. However, similar results were observed in a placebo test that did not control for patient and market-level characteristics.

Finally, the measures of procedural quality used in this study only included clinical outcomes that are measurable in claims data. These measures do not include patient satisfaction or experience, which are important dimensions of quality. Similarly, the procedural complication measures do not identify “successful” procedures. This absence is especially important for colonoscopies, which are key screening mechanisms for detecting colorectal cancer.23,24

Despite these limitations, this study provides initial evidence on the widespread variation in prices and procedural complication rates for three common outpatient surgical services. While several previous studies have documented extensive geographic variations in prices and quality, few studies have examined the association between provider price and quality outcomes. In this setting, a modest but positive relationship was observed between risk-adjusted prices and procedural complication rates.

This finding raises the possibility that the same market characteristics that lead to higher prices may also negatively influence the quality of care. One potential explanation is provider competition. Many health-care provider markets are highly concentrated, which has been linked to higher provider prices.25 If providers compete along both price and quality dimensions, and increased competition incentivizes lower prices and increased quality, then increasing market competiveness may lead to reductions in prices and improvements in quality.26,27 Thus, increased regulatory focus on improving the competiveness of health-care markets may both lead to reductions in prices and improvements in clinical quality. The results of this study also suggest that low-priced providers are not reimbursed for their higher quality outcomes.

With increased emphasis on paying for value, employers and insurers have questioned the value of paying for high-priced providers when alternative providers have lower prices. If differences in prices are not linked to improved differences in clinical outcomes, as this study suggests, then efforts to shift patients to low-priced providers can improve the efficiency of the delivery system by reducing spending while improving the quality of care.

References

Franzini, L. et al. Variation in inpatient hospital prices and outpatient service quantities drive geographic differences in private spending in Texas. Health Services Research 49, 1944–1963 (2014).

Cooper Z, Craig SV, Gaynor M, Reenen JV. The price ain’t right? Hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured. (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015).

Castlight Health. Pricing for the same medical services is all over the map. 2014.

Newhouse, J. P. & Garber, A. M. Geographic variation in health care spending in the United States: insights from an institute of medicine report. JAMA 310, 1227–1228 (2013).

Gottlieb, D. J. et al. Prices don’t drive regional Medicare spending variations. Health Aff 29, 537–543 (2010).

Finkelstein, A., Gentzkow, M. & Williams, H. Sources of geographic variation in health care: evidence from patient migration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, 1681–1726 (2016).

Kessler, D. P. & McClellan, M. B. Is hospital competition socially wasteful? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115, 577–615 (2000).

Fisher, E. S. et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann. Intern. Med. 138, 273–287 (2003).

Fisher, E. S. et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann. Intern. Med. 138, 288–298 (2003).

Hussey, P. S., Wertheimer, S. & Mehrotra, A. The association between health care quality and cost: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 158, 27–34 (2013).

Hollenbeck, B. K. et al. Ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient procedure use among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care 52, 926–931 (2014).

Roberts, E. T., Mehrotra, A. & McWilliams, J. M. High-price and low-price physician practices do not differ significantly on care quality or efficiency. Health Aff 36, 855–864 (2017).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases 40, 373–383 (1987).

Papavasiliou, A. V. & Bardakos, N. V. Complications of arthroscopic surgery of the hip. Bone and Joint Research 1, 131–144 (2012).

French, D. D., Margo, C. E. & Campbell, R. R. Comparison of complication rates in Veterans receiving cataract surgery through the Veterans Health Administration and Medicare. Med Care 50, 620–626 (2012).

Warren, J. L. et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 849–857 (2009).

Halm, E. A., Lee, C. & Chassin, M. R. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann. Intern. Med. 137, 511–520 (2002).

Dimick, J. B., Birkmeyer, J. D. & Upchurch, G. R. Measuring surgical quality: what’s the role of provider volume? World J Surg 29, 1217–1221 (2005).

Manning, W. G. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. Journal of Health Economics 17, 283–295 (1998).

Manning, W. G. & Mullahy, J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? Journal of Health Economics 20, 461–494 (2001).

Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/. (Accessed 9th March 2018).

Chubb, H. & Simpson, J. M. The use of Z-scores in paediatric cardiology. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 5, 179–184 (2012).

Levin, B. et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology*†. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 58, 130–160 (2008).

Rex, D. K. et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2008. Am J Gastroenterol 104, 739–750 (2009).

Gaynor M, Mostashari F, Ginsburg PB. Making health care markets work: competition policy for health care. Brookings 2017.

Gaynor, M., Ho, K. & Town, R. J. The industrial organization of health-care markets. Journal of Economic Literature 53, 235–284 (2015).

Gaynor, M. & Vogt, W. B. Competition among hospitals. The RAND Journal of Economics 34, 764–785 (2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the RAND Corporation and the University of California, Berkeley.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he does not have a conflict of interest.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 473 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whaley, C. The Association Between Provider Price and Complication Rates for Outpatient Surgical Services. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1352–1358 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4506-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4506-7